This is the second post in a series about blockchain market microstructure. The first post discussed how application controlled execution (ACE) can help DeFi tokens capture value in a bunch of interesting ways. Click here to read that post. This post explores how to reduce adverse selection in DeFi markets.

Onchain liquidity has mostly evolved by focusing on one thing at a time. Early on, the main goal was simply to have a counterparty for takers without (a) having to post bids in a central limit order book (CLOB) on Ethereum (where that’s not feasible), and (b) relying on an offchain matching engine (e.g., 0x). Uniswap’s big breakthrough in 2018 was making onchain liquidity open to everyone via automated market maker (AMM) liquidity pools. The tradeoff was that AMMs didn’t always produce the best pricing for every trade.

As time went on, the focus shifted from just having liquidity to improving price quality. Uniswap V2, V3, and now V4 all brought upgrades that made prices better, the biggest one being concentrated liquidity. Then came CLOBs like Phoenix on higher performance L1s and Ethereum L2s.

As new DEXs launched, liquidity became fragmented across many different venues. This led to the emergence of aggregation services, such as 1inch, which routed trades through several DEXs to improve price and reduce slippage.

While the overall market structure has evolved to increase liquidity and tighten prices, another vector has been overlooked: the inefficiency and potential for adverse selection in order flow.

Informed vs. Uninformed Flow

Across all markets, high-frequency trading (HFT) firms and market makers spend millions on data, technology, and research to have a sense of where prices will go in the next few seconds or minutes. In contrast, the average trader typically does not.

Market makers treat order flow differently based on whether it is informed or uninformed. They often lose money when trading against informed (toxic) flow, but they make money by earning the spread when trading against uninformed flow. So, informed order flow is considered toxic to market makers, while random or retail flow is desirable. (Note: We use the term “toxic” in this post to mean less preferred by market makers. It does not connote malign intent or toxicity to a system, but instead based upon the expected response of market makers when they believe flow is informed.)

As we’ve learned from speaking to founders in DeFi, whether order flow is toxic or non-toxic is measured over periods from a few microseconds up to 10 minutes, depending on the asset. If a market maker has enough time to offload risk after trading with you, such as an hour, and your 7-day markout is consistently profitable (but your 1 hour markout is random), in our opinion the market maker likely won’t view you as a toxic trader. For less liquid assets, market makers use a longer time frame to measure toxicity because it takes them longer to offset the risk.

The main issue with toxic order flow is that it raises trading costs for everyone. To protect themselves against toxic flow and sharp traders, market makers widen their quotes, resulting in everyone paying higher spreads.

Structural Inefficiencies in Onchain Order Flow

In traditional markets, achieving a sustainable trading advantage is expensive. HFT firms and hedge funds use fast data feeds, quick connections, colocated servers, and expert teams. This setup is very different from how most retail investors trade, which is through simple, slow user interfaces.

These differences naturally separate order flow via which user interface it comes from. Retail trades are slower because they go through brokers and the public internet. In contrast, hedge funds and HFTs use private, faster networks (the type of private fiber networks which DoubleZero integrates to improve onchain rails for validators). As a result, you can often tell the type of order flow by the access and technology used.

The types of trading segmentation in TradFi don’t exist in the blockchain trading world. Whether it’s a retail user swapping tokens with a browser wallet, an institutional player submitting a programmatic trade, or a more sophisticated player (e.g., a searcher arbitraging markets), all these actions look the same in the public mempool or if they’re sent direct to validators in the case of Solana. There is no mandated, intermediated function (e.g., use of broker, account type, or KYC) to differentiate retail traders from professionals or other more sophisticated players.

If someone is clearly toxic on traditional markets, the broker has all their info and can spot that behavior, then route or price their trades differently or even close an account. Basically, they label them as toxic. Onchain, there are less definitive tools to identify or mitigate adverse selection. Blockchains are pseudonymous, so addresses can be tagged to identify malicious actors; however, protocols themselves (e.g., Uniswap or Drift) are permissionless and sophisticated players can mask activity through scores of wallets and trade from different account addresses.

In crypto, price discovery usually starts on centralized exchanges (CEXs), including derivatives markets. Afterward, arbitrageurs on AMMs bring prices back in line; this arbitrage is inherently adverse selection for market makers although it improves market quality and efficiency by bringing prices back into line across different venues. Onchain CLOBs help because market makers can update their quotes in real time, but this does not fully solve the problem since onchain prices are still often just reacting, even on CLOBs.

Onchain markets are inherently fragmented and decentralized by design. This promotes certain positive qualities, but is challenging for seeking something akin to best execution across all markets. During periods of congestion, retail orders can get delayed or fail to land at all, which often means trading at stale prices or not getting a fill in. Execution quality is not just about quoted price or available liquidity. It also depends on whether your transaction actually makes it into a block, something that historically has not been guaranteed. In fact, in our experience many onchain traders will prioritize landing certainty over price slippage.

Add it all up: no clear segmentation because of how blockchains work, no way to definitively label all of a user’s wallets as toxic, price discovery happening on CEXs, and transaction inclusion hurdles, and you can see the challenge. The onchain market constantly evolves to find better solutions, and as we discuss below, there are several ways to solve these structural problems.

Addressing Adverse Transaction Ordering

Transaction ordering can broadly be bucketed into two categories:

- Value-additive actions—liquidations, backrunning, and CEX-DEX arbitrage, for example. These types of ordering actions deter application bankruptcies and correct price discrepancies, and contribute to a functioning market. While there is no guarantee an individual transaction will receive ideal resolution, these actions improve overall market quality.

- Adverse transaction ordering—NFT or memecoin sniping, front-running, and sandwiching, for example. These types of MEV strategies benefit searchers and validators at the expense of retail users by increasing their costs without positive impact on overall market efficiency.

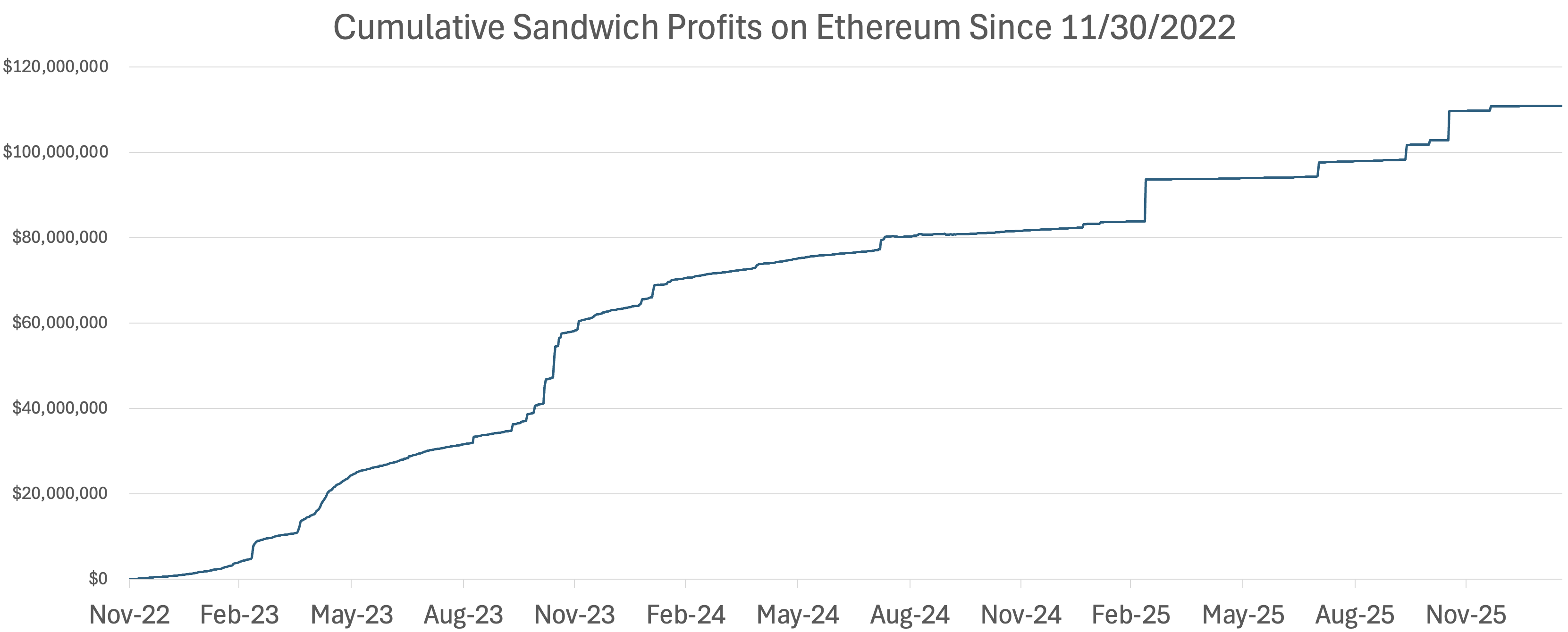

While both value-additive and adverse transaction ordering can result in MEV, sophistication in ordering strategies has resulted in some parties engaging in more adverse transaction ordering strategies. The market has responded. For instance, Jito, the largest client on Solana, chose to turn off their mempool feature because sandwich attacks from searchers were making execution worse for regular users. On Ethereum, sandwiching has also grown into an industrial-scale process. This chart shows cumulative sandwich profits to date since 11/30/2022.

Source: eigenphi.io

These strategies only exist on blockchains because user intent is shown before trades happen. In these cases, searchers are not discovering new information; they’re just taking advantage of what others are about to do. This is the clearest example of adverse selection.

As a result of this visibility, onchain liquidity is often priced as if every trader is informed. As mentioned earlier, this leads market makers and other liquidity providers (LPs) to widen spreads, traders to get worse execution, and less experienced users to subsidize more advanced ones.

Deeper liquidity pools and better overall pricing have come and been beneficial to DeFi. But the default assumption that all flow is informed naturally inhibits best execution for users because spreads widen for everyone. All order flow becomes less desirable.

So What Can DeFi Do About It?

There is no single silver bullet. Inefficient order flow is a natural byproduct of public blockchain transparency and the block building process. Still, there are several ways to adjust incentives and make the system harder to exploit in ways that disadvantage ordinary users and harm network efficiency.

Broadly, we’ve separated these strategies into six categories: you can (1) delay execution, (2) hide intent, (3) segment flow, (4) price risk dynamically, (5) refuse specific trades during certain market conditions, or (6) try social coordination to solve misalignment. Most production systems use some combination of these, and none are necessarily free.

Below, we’ll break down each of these approaches, the models within each, and the trade-offs associated with them.

Delaying Execution

The simplest way to cut down on adverse transaction ordering is to make it less valuable to react first. If searchers can’t spot an order and trade against it quickly within a short window, many adverse transaction ordering strategies won’t work. That’s the basic idea behind speedbumps.

In traditional markets, participants move at different speeds. Retail orders go through brokers and the public internet before reaching the matching engine, while HFTs use colocated servers and private fiber connections. This gap makes it hard to profit from reacting to retail trades in real time, unless the HFT is purchasing order flow from brokers. Onchain, though, everything shows up together, at the same speed, and everyone can see it. Speedbumps try to bring back that separation.

One way to delay execution is by batching. Trades are gathered over a short period and then settled at a single price. Since everyone in the batch gets the same price, it doesn’t matter who is first or last, and sandwiching mostly goes away. The downside of this approach is that markets become slower and less responsive, which can be problematic during periods of volatility.

Another model is to add delays to execution. There are a few different flavors of this.

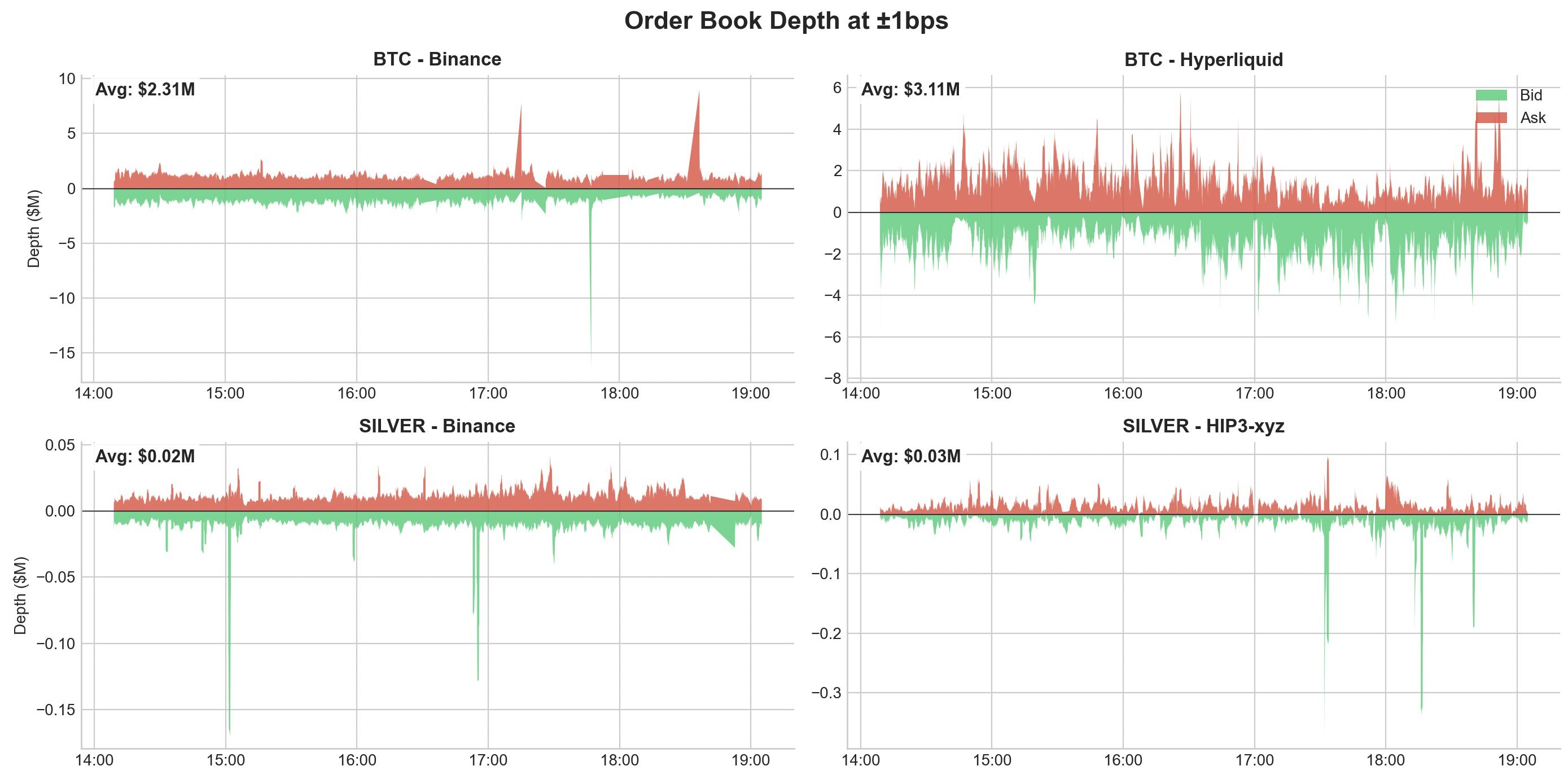

The first way is to let market makers cancel orders first, like Hyperliquid does. This is also referred to as “maker priority.” The idea is that market makers should be able to pull or update their quotes to avoid trading at stale prices. By letting cancels execute before new taker orders, Hyperliquid lowers the risk for market makers during fast market moves. This also makes it cheaper for market makers to offer tighter spreads during normal market conditions, since they’re less worried about being caught offsides if volatility picks up. In fact, in our experience, this has been a big reason why Hyperliquid is, in fact, hyper liquid, even relative to its CEX competitors.

Source: Blockworks

The second approach is designed for takers instead of market makers—i.e., “taker priority.” Instead of making everyone wait, the exchange creates a fast lane for trades that need to move quickly, such as arbitrage, liquidations, or other time-sensitive strategies. These trades use this priority lane, which often comes with higher fees or special rules. Market makers who use this lane know they are likely on the other side of toxic flow and can adjust their prices accordingly. This is a market-based substitute for some of the structural broker controls discussed earlier.

Speedbumps are now showing up in prediction markets too. A fascinating comparison to look at is Kalshi and Polymarket. Kalshi leads sports volume and open interest by ~2x. However, Polymarket in some cases has tighter liquidity closer to midbook because they apply a 3 second delay on market orders. This reduces the amount of adverse selection that Polymarket liquidity faces.

Overall, delay-based methods don’t eliminate toxic order flow, but they do determine where it appears and who pays the price. Batching takes away the advantage of being first, giving market makers cancellation priority protects them from stale prices, and priority lanes make fast (potentially informed) traders show themselves. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: Helps prevent latency races, reduces sandwich attacks, and protects passive liquidity.

- Cons: Sometimes breaks atomic composability, and batching can slow down matching for uninformed traders.

Hiding Intent

Delaying trades may slow others’ reactions, but concealing intent prevents any reaction entirely. Adverse transaction ordering happens when information leaks ahead of trades. In these situations, searchers aren’t really uncovering new information; they’re simply exploiting knowledge of others’ transactions before commitment to the blockchain. As a result, when intent remains hidden, much of the harmful adverse transaction ordering can be eliminated.

In traditional markets, a lot of trades take place out of sight. Retail orders are typically processed privately, matched off-exchange, or sent to wholesalers before they show up in the public CLOB. Onchain, the process is different: intent is visible by default. When someone submits a transaction to a public mempool, information like the asset, size, direction, and urgency can be seen by anyone. So the goal of hiding intent is to address this issue.

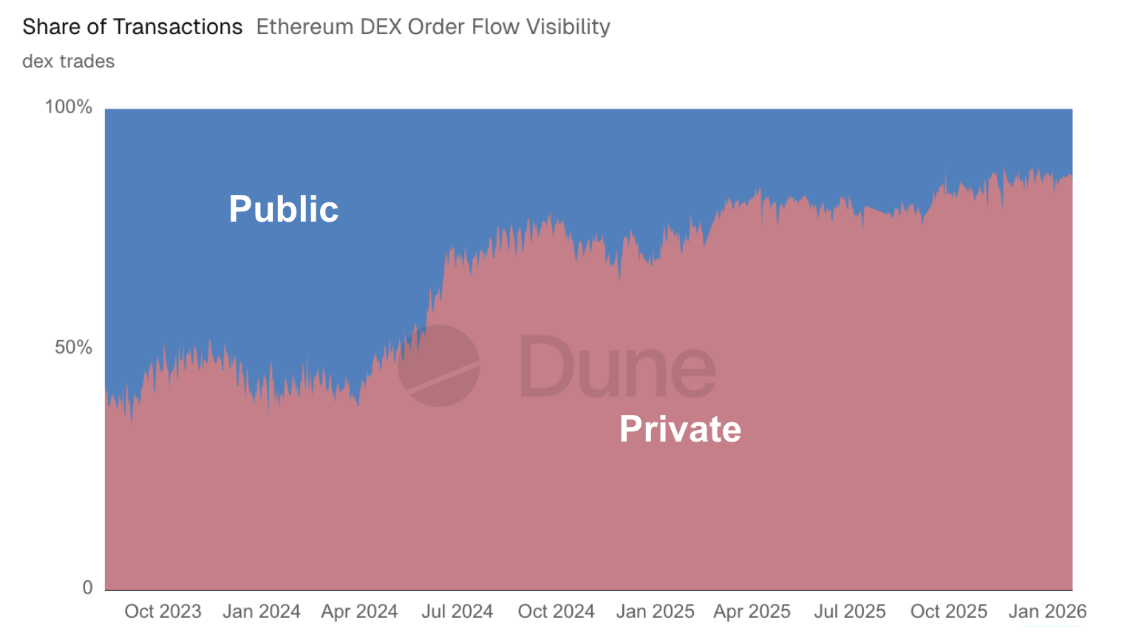

One way to hide intent is private routing. Here, users send orders to a private relay, order flow auction, or a matching system rather than the public mempool. The transaction is only revealed when it’s executed, and in some cases the system backruns user transactions and pays a rebate. Systems like Flashbots and MEV Blocker on Ethereum use this model. By keeping intent private, this method stops common sandwiching and front-running, but it also means users must trust the entity that runs the relay and manages the transactions. Importantly, the vast majority of order flow on Ethereum transmits through a private channel at this point:

Source: Dune Analytics, @dataalways

Another approach is commit-reveal. Users first submit a cryptographic commitment, then reveal the full trade details later. Intent stays hidden during the commit phase, and execution only happens after the reveal. This works in theory, but it’s clunky in practice. It requires two transactions, worsens UX, can fail if the reveal never happens, and breaks atomic composability. Any workflow that relies on everything happening in one transaction like swap → borrow → repay becomes difficult or impossible.

Another approach is to use encrypted mempools, which keep transaction details hidden until they are added to a block. This model helps maintain public ordering and stops information from leaking before trades happen and they can be powered by trusted execution environments (TEEs) or fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). However, it adds complexity and isn’t yet ready for widespread use. Even strong supporters admit that public chains would need major changes, so they suggest introducing this idea gradually. This is the biggest and most important idea, but also the hardest to implement. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: Completely stops sandwiching and front-running, and also prevents pre-trade information from leaking for other reasons.

- Cons: Requires trusting relays, and encrypted mempools are very difficult to implement from a technical standpoint.

Flow Segmentation

This model closely resembles how traditional markets operate (where retail liquidity is either kept in-house or sent to wholesalers, while toxic or fast trades go to public exchanges, dark pools, and similar venues).

Onchain, routing needs to work without brokers, accounts, or user identities. The aim is not to judge users, but to sort orders by how they come in and what they require from the system.

One way to do this is by using explicit flow segmentation. For example, conditional liquidity, an idea from our portfolio company DFlow, lets frontends, wallets, and brokerages tag addresses as retail and non-toxic. This allows them to earn part of the spread because market makers charge these users lower fees. For example, an AMM might charge everyone 30bps, but only 15bps to tagged retail wallets. The wallet provider could then add 5bps on top. This approach helps the AMM separate toxic and non-toxic flow, gives retail soft flow better prices, and lets the wallet earn money without max extracting from users. Everyone wins.

For this system to work, there must be an open market mechanism. If wallets keep tagging addresses that turn out to be toxic, they will eventually lose privileges with the LP, such as an AMM or propAMM, and likely will stop receiving reduced fees on their tagged flow.

Paradex introduced another version of this idea with their Retail Price Improvement (RPI) model. RPI is a maker order type that displays post-only limit orders in the UI, but hides them from API access, which is how most toxic flow trades. Binance actually followed Paradex’s lead and implemented a similar model for their futures product.

One other interesting model is enabling post-fill canceling by makers. Basically market makers could quote two different prices, and in the tighter price they would have the option to cancel a trade within 1 second after matching. If the counterparty is toxic, they obviously would care about what the price does in a second timeframe (and so they wouldn’t accept the tighter quote), but for random retail flow they don’t care if it takes a few seconds to fill. This would enable market makers to quote tighter for slower, less toxic flow.

The final approach here is path-based routing, where the way an order is sent shows how urgent it is. Orders sent through private relays, fast lanes, or solver systems are seen as needing speed and are matched with liquidity that expects more toxic flow. Slower orders go to tighter, more passive liquidity. In this setup, users choose for themselves: if you need speed, you show it and pay for it through higher fees or price impact. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: When done right, segmentation benefits everyone and removes the shared cost caused by toxic takers.

- Cons: It’s hard to segment accurately because toxic traders try to hide, and sometimes liquidity fragments if informed and uninformed users can’t access the same pools.

Dynamic Pricing

If a passive liquidity source can’t fully guard against the consequences of toxic flow, it should at least use dynamic pricing. For instance, it can widen spreads when there is more risk of adverse selection, like during high volatility, and tighten when markets are stable.

In traditional markets, this adjustment happens all the time. Market makers widen spreads when volatility rises, reduce liquidity when uncertainty is high, and quote more actively when things settle down. Onchain AMMs, however, began with fixed fees based on the idea that risk is always the same. This approach works when trades are mostly random, but fails when there is toxic trading.

LFJ’s Liquidity Book is a good example of dynamic pricing. Rather than using a fixed swap fee, Liquidity Book changes its fees based on volatility. If prices move quickly or a pool is under stress, fees go up automatically. When markets are calm and balanced, fees go down. This means LPs get paid more when they face higher risks from adverse selection.

Dynamic fees can create a feedback loop: higher fees lower trading volume, which can make price discovery harder when prices are moving quickly and drive more trades to private or request for quote (RFQ)-style models. This can hurt price discovery making toxic flow attractive even at higher fee tiers. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: This is the best way to protect passive LPs, stays neutral without favoring anyone, and is directionally similar to what market makers do on CLOBs.

- Cons: It can make trading more expensive for regular users during volatile times, even if they don’t have extra information, which can cause price disparity. It also doesn’t solve intent leakage.

Refusing Flow Altogether

Early DeFi systems were built on the idea that liquidity should always be available, no matter what. As long as a trade met the contract’s rules, it would go through. This made sense when the main goal was just to get markets up and running. But as the forest gets darker, this approach stops working. In these situations, making liquidity always available ends up letting better-informed traders take advantage of everyone else.

Newer designs don’t treat liquidity as something that’s always available. Instead, they set explicit rules for when liquidity shows up. Availability can depend on volatility, recent price moves, or whether trades go through a protected path like an RFQ or private relay.

Perpetual futures are a good example of this. In perp markets, LPs and risk engines actively manage exposure. They watch volatility, trade direction, and inventory. When markets move quickly or flow becomes one-sided, liquidity gets more expensive or disappears by design.

This shows up in a few predictable ways. Position limits tighten as volatility rises. Pricing skews to block one side of the book, and funding rates push traders to rebalance. Additionally, LPs cap how much net exposure they’re willing to carry. In extreme cases, protocols pause one side of the market while leaving the rest open.

The point of refusing flow isn’t fragility, it’s honesty. Instead of pretending liquidity can always be priced fairly, the system admits that some conditions are too risky. That gives LPs confidence to take more risk when markets are calm.

This looks a lot like circuit breakers in traditional markets. Both recognize that keeping liquidity open at all times can do more harm than good. The difference is that DeFi can apply these rules programmatically in different conditions without shutting down the entire market.

Another clear example of refusing flow altogether is just-in-time liquidity (JIT). JIT is a type of liquidity provision where an active LP monitors the mempool, deposits a tight band of liquidity, absorbs a swap, and then withdraws right after. While passive LPs always keep liquidity live and open, JIT LPs refuse flow except for very specific trades. This can harm passive market maker returns, but also gives better prices for uninformed traders who are chosen to be traded against by JIT. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: Lets markets offer tighter pricing in normal times, makes risk limits clear, and works well for derivatives DEXs where one-sided risk can be a big problem. JIT makes prices better for uninformed traders, specifically those executing large swaps.

- Cons: Liquidity can disappear, which has obvious downsides. It’s important to set the right parameters so the market doesn’t shut down during normal trading periods. Additionally, JIT LPs can reduce non-toxic flow from passive LPs.

Social Pressure

Most of the approaches discussed so far – delay, hiding intent, flow segmentation, dynamic pricing, and flow refusal – are protocol- and exchange-level design choices. They’re put in place by protocols and venues, and their effects are limited to a specific pool, market, venue, or execution path. Social coordination is different. It usually works at the base layer, involving validators, sequencers, and block builders.

Social coordination depends on cultural norms, reputation, and group pressure to discourage harmful behavior, even if it’s technically allowed. Rather than changing how an application executes trades, it tries to influence which transactions are included in blocks and how they’re ordered. It is reordering the social norms of ordering, rather than technical changes to the ordering machines.

In traditional markets, this layer is built in. Exchanges, brokers, and market makers work within a set of expectations about abuse, fair dealing, and long-term relationships. But in crypto, validator and searcher functions are generally permissionless, and parties often come and go quickly. If a strategy is profitable and allowed by the protocol, people will use it.

Social coordination tries to bring back some of those missing norms at the base layer. There are already early examples, such as public dashboards that track sandwiching behavior, informal lists of harmful builders, and community pressure on validators to avoid certain adverse ordering strategies (see ibrl.wtf and sandwiched.me, as examples). In some ecosystems, stakers reward validators who commit to clean execution and punish those who don’t by moving their stake elsewhere.

To be fair, social coordination has built-in limits. It can’t be programmatically enforced, it depends on repeated interactions and reputation, and it becomes weaker as validator groups grow and become more anonymous. If the profits are high enough, people will eventually break the rules.

Because of this, social coordination works best as a base layer addition to application-level design, not as a replacement. It can help limit the worst behaviors, give time for better solutions, and set expectations for what is acceptable. But it can’t reliably maintain execution quality on its own. Our assessment of the pros and cons:

- Pros: Provides faster feedback without needing tech or financial changes, and helps stop the worst types of adverse ordering activity.

- Cons: Raises questions about censorship on the chain itself, isn’t enforceable, and leaves venues dependent on validators and stakers down the stack, meaning they don’t control their own destiny.

The Design Space

Each of the six ways to manage adverse ordering activity appears to solve real problems, but they focus on different challenges and operate at various levels. The right choice depends on what a protocol wants to optimize for, whether it’s UX, composability, neutrality, capital efficiency, decentralization, type of liquidity provisioning, or something else.

The main takeaway is that there is no one perfect solution. These are a few of the tools we’ve found to help with the problem of toxic order flow in DeFi, and there are probably others as well. We think both spot and derivatives DEXs should explore these models, iterate on them, and consider using several methods, depending on their market structures.

These market microstructure opportunities are nuanced and critical, and we believe getting them right can deliver massive venture-scale outcomes. We want to work with the best developers to tackle these problems together and create positive sum outcomes for DeFi. If you’re working on this, please reach out to us on X at @spencerapplebau and @shayonsengupta.

In our next post in our series on onchain market structure, we’re going to examine how real world assets will come on chain over time. There are many teams trying to bring equities, FX, credit, commodities, treasuries, etc to blockchains. We will examine the various models (synthetics, custody model, primary issuance, etc), the path dependency for each asset class, and how we expect this to evolve.